To be effective and secure participation, a global climate change agreement needs to be perceived as fair by the countries involved in it. The Paris Agreement approached differentiation of countries’ responsibilities to address climate change by departing from the rigid distinction between industrialised and developing countries through the inclusion of ‘subtle differentiation’ of specific subsets of countries (e.g., Least Developed Countries) for certain substantive issues (e.g., climate finance) and/or for specific procedures (e.g., timelines and reporting). In this article, we analyse whether the self-differentiation countries followed when formulating their own climate plans, or nationally determined contributions (NDCs), is consistent with the Paris Agreement’s subtle differentiation. We find that there is consistency for mitigation and adaptation, but not for support (climate finance, technology transfer and capacity building). As NDCs are the main instrument for achieving the Paris Agreement’s long-term goals, this inconsistency needs to be addressed to allow subsequent rounds of NDCs to be more ambitious.

While countries are formally equal in the United Nations (UN) climate negotiations, their contribution to greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, development needs, and vulnerability to climate change vary greatly. These differences have been addressed by acknowledging countries’ ‘common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities’ (CBDR-RC) in the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

A dichotomous interpretation of CBDR-RC enabled international agreement on the Convention and its Kyoto Protocol. Industrialised (Annex I) countries committed to absolute emission reduction or limitation targets, whereas all other (non-Annex I) countries had no such obligations. This rigid distinction, however, does not reflect the dynamic diversification among developing countries since 1992, as reflected in diverging contributions to global emissions and economic growth patterns (Deleuil, 2012; Dubash, 2009). This has led Depledge and Yamin (2009, 443) to label the Annex I/non-Annex I dichotomy introduced by the UNFCCC ‘dysfunctional’ and ‘the regime’s greatest weakness’.

The Paris Agreement did not dissolve this dichotomy. It also did not introduce new ways of allocating emissions among countries, such as convergence towards equal per capita emissions, or differentiating based on survival versus luxury emissions (see Kartha et al. 2018; IPCC, 2013). Nevertheless, the Paris Agreement moves on from the 1992 dichotomy in at least three ways.

First, it follows a more nuanced and dynamic interpretation of CBDR-RC. The Paris Agreement distinguishes between ‘developed’ and ‘developing’ countries instead of Annex I and non-Annex I countries. This allows developing countries to increase their ambitions over time without formally ‘graduating’ to Annex I (Voigt and Ferreira, 2016). This is further reflected by the Paris Agreement’s addition of the phrase ‘in the light of national circumstances’ to the notion of CBDR-RC: as countries’ circumstances evolve, so too will their common but differentiated responsibilities (Rajamani, 2016).

Second, the Paris Agreement introduces bounded self-differentiation of countries’ responsibilities through their national climate action plans, known as nationally determined contributions (NDCs). These climate action plans are universal (i.e., each country formulates one), bottom-up (i.e., countries set their own priorities and ambitions) (Mbeva and Pauw, 2016) and ‘contributions’ rather than the harder ‘commitments’ commonly used in international treaties (Rajamani, 2015). Self-differentiation is bounded by the notions of ‘progression’ and ‘highest possible ambition’ that NDCs need to abide by (Voigt and Ferreira, 2016).

Third, the Paris Agreement differentiates between countries in a context-specific and often subtle manner. We define this ‘subtle differentiation’ as subtlety towards specific subsets of countries (e.g., Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and Small Island Developing States (SIDS)) on specific issues (e.g., adaptation finance) and/or procedures (e.g., timelines and reporting).

Inconsistency between subtle differentiation of the Paris Agreement and self-differentiation of NDCs could, at a minimum, result in countries refusing to make their NDCs more ambitious because they perceive other countries’ NDCs as less ambitious (see Grieco et al., 1993; Mearsheimer, 1994). This in turn, may create negotiating difficulties in the run-up towards updating NDCs by 2020 and beyond. At worst, it could put the Paris Agreement’s ambition mechanism at risk: if countries are cautious or reluctant to ratchet up their ambition over time, it is more likely that the long-term goals of the Paris Agreement will be missed.

This article offers a novel approach that complements existing research on how to ensure fairness in international climate policy through NDCs. Existing research includes the bottom-up approach followed by Winkler et al. (2018), who study countries’ justifications for fairness in NDCs. They show that countries have put forward a wide variety of hardly substantiated indicators and approaches. By contrast, the top-down approach by Du Pont et al. (2017), Brown et al. (2018), Zimm and Nakicenovic (2019) and Climate Action Tracker (n.d.) compares NDC ambitions with global emission reduction goals under different equity assumptions. Such assessments make normative judgements on emission allocations that have limitations (Kartha et al., 2018), especially in the absence of an operational definition of CBDR-RC under the UNFCCC. By examining consistency with the subtle differentiation put forward in the Paris Agreement, we seek to provide a substantiated approach on how to ensure fairness through NDCs, while eschewing normative judgements on what constitutes a ‘fair’ contribution.

Reflecting a narrow framing of climate change as an environmental (i.e., pollution control) problem rather than a developmental problem (see Hermwille et al., 2017; Makomere and Mbeva, 2018), the fairness of climate action through CBDR-RC has typically been discussed in the context of mitigation (Ciplet et al., 2013; Klinsky and Winkler, 2014). However, the notions of equity and CBDR-RC in the UNFCCC are not limited to mitigation (UN, 1992, Article 3.1). Considerations of equity should therefore encompass other elements of international climate policy, such as vulnerability to climate impacts, finance, and technology transfer (BASIC Experts, 2011; Climate Action Network, 2013; Klinsky and Winkler, 2014; Pauw et al., 2014).

That said, the 1992 UNFCCC differentiates between Annex I Parties with respect to some of the core mitigation commitments, such as the commitment to adopt policies and measures in Article 4.2(a). More importantly, the commitments in the Convention were based primarily on whether countries were included in Annex I (a list of countries that then comprised the OECD plus additional states undergoing the process of transition to a market economy) or Annex II (a subset of Annex I, including the then-OECD countries). Other country categories are nonetheless mentioned. For instance, a wide range of developing country categories is listed in the context of considering the impacts of climate change and the impact of implementation of response measures, including small island countries, countries with fragile ecosystems, fossil fuel-producing countries, landlocked countries, and so on (Article 4.8). Furthermore, Parties need to take into account the specific needs and special situations of LDCs in the context of technology transfer (Article 4.9).

The 1997 Kyoto Protocol included emission reduction or limitation targets for Annex I countries, but not for non-Annex I countries. The Protocol therefore only cemented the mitigation focus and strengthened the dichotomy.

The non-legally binding 2009 Copenhagen Accord that only received support of 114 out of 194 Parties (UNFCCC, 2010)—in many ways a precursor for the Paris Agreement (Bodansky, 2016)—signaled a move away from the Annex I/non-Annex I dichotomy by suggesting that LDCs and SIDS have more flexibility than other non-Annex I countries in implementing mitigation actions (UNFCCC, 2010: para. 5). Furthermore, it prioritises adaptation finance for the ‘most vulnerable developing countries’, specifically mentioning LDCs, SIDS and Africa (UNFCCC, 2010: para. 8). Lastly, ‘incentives’ should be provided for ‘low-emitting’ developing countries (without defining these), for them to continue low-emission development (UNFCCC, 2010: para. 7).

Compared to the UNFCCC, the Kyoto Protocol, and even the Copenhagen Accord, subtle differentiation is much more prominent in the 2015 Paris Agreement (see Table 2 in the online supplementary material). There are 19 instances of subtle differentiation with respect to subsets of countries, certain substantive issues or procedures (see Table 1). It is most evident with respect to finance and capacity building, but also apparent with regard to mitigation, adaptation, technology transfer (both in the preamble and Article 13, but not in Article 10 on technology transfer) and the transparency framework. In that sense, subtle differentiation covers the main aims of the Paris Agreement as outlined in Article 2 (mitigation, adaptation and finance), even if subtle differentiation is absent in this provision itself. No differentiation is visible in Article 8 on loss and damage, because it does not include any commitments for Parties other than ‘enhancing understanding’ (UNFCCC, 2015, Article 8.3).

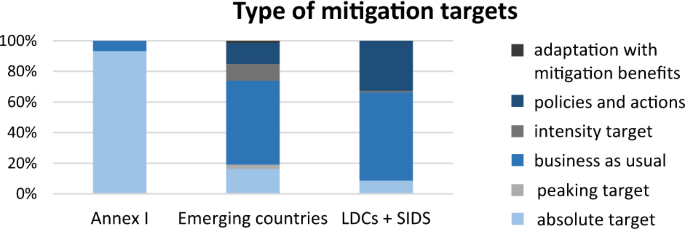

The emerging countries take on various types of commitments, where a peaking target (3% of emerging countries) is arguably the second-most stringent type of commitment. A majority of both the emerging countries (55%) and the LDC + SIDS (58%) set business-as-usual type of targets, meaning they aim to reduce their emission levels below their projected emissions under a business-as-usual scenario. Among LDCs and SIDS, the second largest type of target is ‘policies and actions’ (33%). This is one of the least stringent types of commitments, even if the targets themselves can be ambitious for the respective countries (Hof et al. 2017). However, the type of target can be considered to reflect the subtle differentiation in the Paris Agreement (see Article 4.6 and Table 1), which states that LDCs and SIDS may prepare and communicate strategies, plans and actions for low GHG emission development reflecting their special circumstances. The above does not take into account to what extent the implementation of contributions is dependent on external support (see Section 3.2) as it is out of the scope of this study. Zimm and Nakicenovic (2019) and Pauw et al. (2019) analyse the implications of conditionality on feasibility and equity of NDC implementation in more detail.

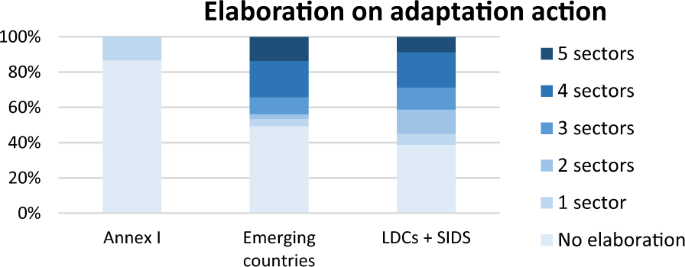

The inclusion of adaptation in NDCs is cascading in this same sequence of country categories. Following the NDC Explorer (see the supplementary online material for further details), the inclusion of adaptation is defined as the explicit elaboration on actions, plans or strategies for the five most common adaptation sectors in NDCs: water, agriculture, health, biodiversity/ecosystems and forestry. This reflects whether countries consider adaptation a ‘key component of and contribution to the global response to climate change’ (UNFCCC, 2015; Article 7.2 and Table 1).

This article cannot indicate what ideal ‘cascading’ would look like for adaptation in terms of consistency with the subtle differentiation in the Paris Agreement, primarily because the Paris Agreement does not make communicating information on adaptation mandatory in NDCs. In addition, detailed baselines of countries’ adaptation efforts and needs would be required. Although emerging countries have the highest percentage (14%) of NDCs that include actions, plans or strategies for all five sectors (see Fig. 2), LDCs and SIDS include adaptation most strongly. The validity of the findings is underlined by similar cascading with regard to NDCs’ mentioning of vulnerable sectors and climate risks, or the number of countries that include adaptation cost indications in their NDCs (see Pauw et al. 2016).

Another way in which subtle differentiation with respect to adaptation is put in practice is the recognition of the importance of support for and international cooperation on adaptation efforts, in Article 7.6 of the Paris Agreement. This will be dealt with in the next section.

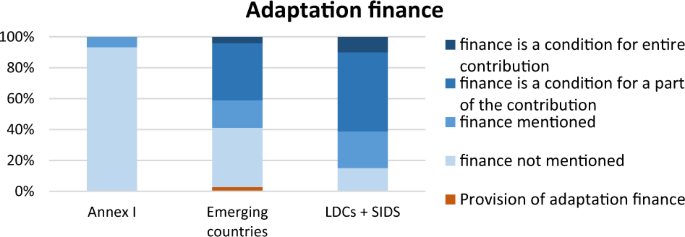

Results for climate finance, technology transfer and capacity building also look as if they cascade (see Figs. 3 to 6). However, while cascading is clearly visible for requests for support, no cascade can be observed for pledges for support. As in the case of adaptation, this article cannot prescribe what ‘ideal’ cascading would look like with respect to consistency with the Paris Agreement’s subtle differentiation. On the one hand, the Paris Agreement does not include indications that would justify such prescriptions. On the other hand, it is outside the scope of this article to provide an expectation based on the extent to which support requests and provision in NDCs reflect either existing flows of support, or the needs of countries (see e.g., Betzold and Weiler (2017) and Klöck et al. (2018) for debates on climate finance allocation). Below we describe the cascading for both requests for support and later for provision of support.

In terms of requests for support, cascading is clearly visible for both adaptation finance (See Fig. 3) and mitigation finance (see Fig. 4). Apart from Turkey, Annex I countries do not mention adaptation or mitigation finance. Self-differentiation is consistent with the subtle differentiation of Article 9.4 in the sense that 61% of the LDCs and SIDS indicate that they can only implement their adaptation contribution if this is partly or completely financed through international support, whereas only 41% of the emerging countries does so. This difference is similar for mitigation finance (80% versus 60%).

The other forms of subtle differentiation related to finance cannot be analysed in NDCs: communication outputs (Article 9.5 and 9.7) are not described in NDCs, nor are simplified approval procedures and enhanced readiness support (Article 9.9).

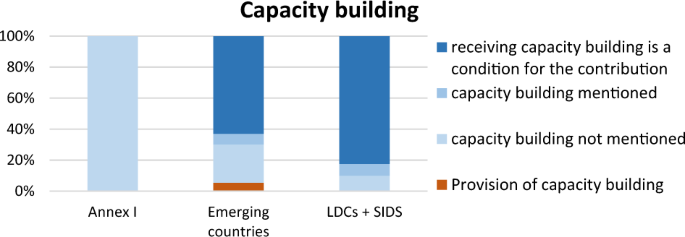

Similar to mitigation finance, 63% of the emerging countries and 83% of the LDCs and SIDS indicate that the implementation of their NDC depends on receiving capacity-building support (see Fig. 5). This self-differentiation is consistent with Article 11.1 (see Table 1).

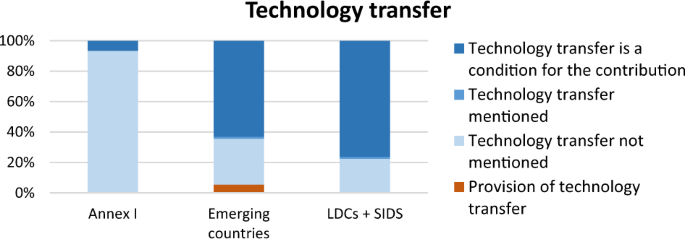

Lastly, self-differentiation of support for technology transfer in NDCs is consistent with the differentiated specific needs as indicated in the Paris Agreement (UNFCCC, 2015; preamble). Overall, 63% of the emerging countries and 76% of the LDCs and SIDS make their contributions dependent on receiving technology transfer (see Fig. 6).

However, self-differentiation on provision of support in the NDCs is not consistent with the subtle differentiation of the Paris Agreement. None of the Annex I countries describe the provision of financial support in their NDCs, whereas some ‘other Parties’ (UNFCCC, Article 9.2) do, in this case the emerging countries of Brazil, Chile and Panama. Similarly, not a single Annex I country describes the provision of support for capacity building, but three emerging countries do. This is not consistent with Article 11.3 of the Paris Agreement, which describes that all Parties should cooperate to enhance the capacity of developing countries, and that developed countries should enhance support for capacity-building actions in developing countries. Finally, none of the Annex I countries state that they will provide technology transfer in their NDCs, whereas four emerging countries do.

So while potential recipient countries describe their need for support in their NDCs, potential donor countries hardly document their intentions to provide support. It thus appears that in terms of financial support, self-differentiation through NDCs is not consistent with the subtle differentiation in the Paris Agreement. The Paris Agreement carefully balanced increased mitigation action (and associated transparency requirements) by developing countries with increased support by developed countries. Indications that financial support is not forthcoming could, in line with Pauw et al. (2019), result in recipient countries refusing to make their NDCs more ambitious, as well as tensions between country groupings at the UNFCCC negotiations.

The preceding analysis demonstrates that self-differentiation in the NDCs is consistent with subtle differentiation of the Paris Agreement, except for the provision of support (finance, capacity building and technology transfer). This inconsistency raises two important questions in the context of the updating of NDCs by 2020.

First, should future NDCs include information about the provision of financial, capacity-building and technology transfer support? It can be argued that climate finance, technology transfer and capacity building increase the global ambition to address climate change, and therefore, consequently contribute to achieving the goal of the UNFCCC (Pickering et al. 2015; Rai et al. 2015). However, developed countries have for long maintained the position that NDCs should not include information on the provision of finance (IISD, 2014, 2018), and the NDC formulation guidance adopted at the climate conference in Katowice, Poland in 2018 does not require countries to do so (UNFCCC, 2018). Indeed, it can be argued that there are other reporting formats to communicate the provision of support, including the new ex ante climate finance communication introduced in Article 9.5 of the Paris Agreement and the Biennial Transparency Reports (the first of which are due by the end of 2024) pursuant to Article 9.7 and Article 13.10. However, while the ex ante information arguably fulfils a similar function to what we suggest here, the ex post information reported under the Paris Agreement’s transparency framework serves a different purpose, namely to show whether donor countries deliver on the support they have pledged. In addition, when countries indicate their planned support around the same time that developing countries are considering increasing their own ambition can offer importance reassurances to developing countries that support for them to implement their NDC will be forthcoming. Finally, including information on the provision of support for 5 years—rather than for every 2 years—arguably also strengthens the medium-term predictability of finance.

Second, is the Paris Agreement’s ambition mechanism being undermined because self-differentiation on the provision of support is not consistent with the subtle differentiation in the Paris Agreement? We argue it may well be. One-hundred-and-thirty-six developing countries have indicated that the implementation of their NDCs is dependent on at least one type of international support (see Pauw et al., 2019), meaning that they cannot be held to account for failing to implement their NDC if they do not receive this support. More concretely, in reporting on the implementation and achievement of their NDCs under the transparency framework of Article 13, they can point to these conditions in their NDCs.

At the same time, developed countries that provide international support can also not be held to account for the implementation—or lack thereof—of such conditional NDCs by developing countries. In other words, developing country NDCs could be left unimplemented and no one would be accountable. The provision of ex ante information by developed countries about their planned support through other means of communication (e.g., Article 9.5) might improve the implementation of NDCs in developing countries, but this does not clarify who can be held to account as long as such support is not earmarked for NDC implementation. A consequence of developing country failure to implement and achieve its conditional NDC may be finger pointing between developed and developing countries; a situation that could be prevented by developed countries explicitly including support for NDC implementation in their own NDCs.

These two questions need to be addressed politically. If self-differentiation is consistent with subtle differentiation, the Paris Agreement’s CBDR-RC compromise would be operationalised, and NDCs would be able to fulfil their role as main vessels to implement the Paris Agreement. Therefore, we recommend that developed countries include in their NDCs their planned support to developing countries for NDC implementation (Pauw et al. (2018); UN-OHLLRS (2019); UNESCO (2018); UNFCCC (2019); UNFCCC (2014); UNFCCC (2013); UNFCCC (1997); United Nations (1992)).

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available in through the NDC Explorer (10.23661/ndc_explorer_2017_2.0). See: www.NDCexplorer.info.

We also thank the audience at the 2018 Earth System Governance Conference, where an earlier version of this article was presented. Finally, we thank the Frankfurt School of Finance and Management, the University of Eastern Finland and the African Centre for Technology Studies for their financial contribution to make this article available open access. KM further acknolwedges funding from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), through the Green Talents Fellowship, for a research stay at the German Development Institute/Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE) during the early stages of this research.